I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit…

China’s Leading Small Group on Carbon Neutrality: Why Is It Needed?

- China’s new Leading Small Group (LSG) on peak carbon and carbon neutrality was announced on the 27th May.

- LSGs are informal mechanisms that allow for high-level coordination between different departments and local governments on specific policy areas.

- The LSG on carbon neutrality includes several key ministries and significant political figures, and is focused on a challenge that President Xi has personally tied himself to – all of which should grant it strong influence compared to other LSGs.

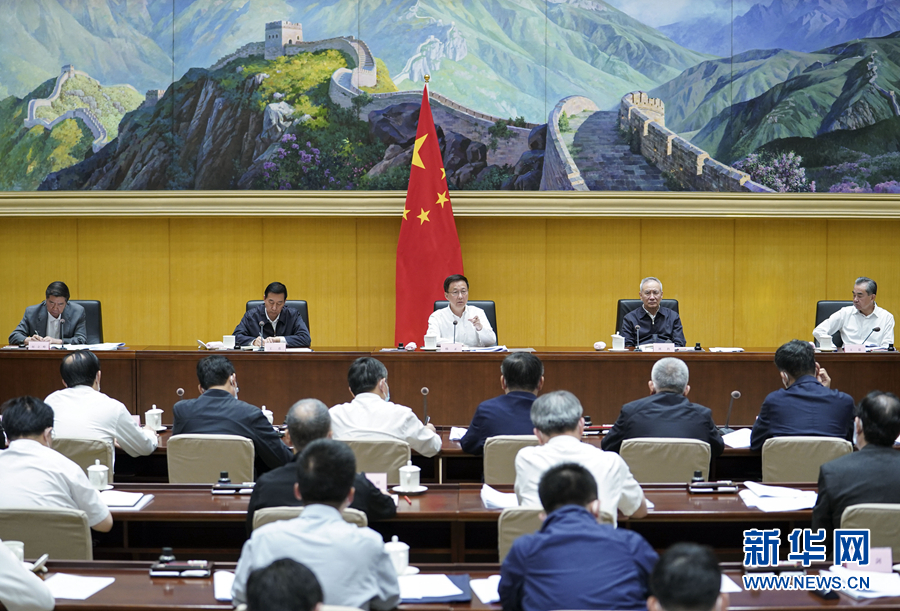

On the 27th May, China’s Leading Small Group (LSG) for peak carbon and carbon neutrality (PCCN) met for the first time. Headed by the Politburo Standing Committee member and Vice Premier Han Zheng, the group also brings together many other political heavy weights, such as Vice Premier Liu He, State Councillors Wang Yong and Wang Yi, and Director of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) He Lifeng.

Together, their mission is to figure out exactly how China will reach its goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2060. The establishment of the group signals a greater commitment from the Chinese leadership to preventing climate change. But how exactly will the group contribute to meaningful policymaking and effective implementation?

What are China’s LSGs?

LSGs are a task force of influential policymakers centred on a particular area of focus. Although the Chinese government is often seen by outsiders as a monolithic, highly coordinated organisation, there are significant areas of debate and fragmentation. LSGs are intended to cut through the noise of competing interests and differing policy priorities between departments and different levels of government by bringing various leading figures together.

Although LSGs are strongly associated with President Xi Jinping’s personal style of governance, they aren’t anything new. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long had the tradition of establishing small groups to deal with specific or pressing issues. In 1958, the CCP Central Committee issued a notice on setting up five groups on finance and the economy, politics, foreign affairs, science, and culture and education which reported directly to the Politburo and the Secretariat.

Many LSGs were inactive during the 1960s, but revived in late 1970s as China began to reform and open up. In particular, the LSG for Finance and the Economy was resumed in 1981 (and would later be upgraded into the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission in 2018 with President Xi as the head). This was followed in 1986 by an LSG focused on attracting foreign investment (although this no longer seems to be active). Under President Xi, LSGs have proliferated to include the famous LSG on Comprehensively Deepening Reform and the LSG on Integrated Circuits.

(photo from xinhua news website)

How useful are LSGs?

Central LSGs are usually headed by the president, premier, a vice premier, a Politburo member or a state councillor. Although meant to be temporary and informal, many central LSGs do wield significant power, especially in terms of drafting and reviewing policy documents, setting out policy priorities and ensuring different departments are aligned on policy directions.

For example, the central LSG on Finance and the Economy was responsible for the preparations for the party’s annual economic work conference, and working with the NRDC on the formulation of annual and five-year plan proposals. In particular, it is famous for adding clauses on supply-side reform of the economy into the 13th Five-Year Plan just before launch.

Aside from heading the LSG for PCCN, Han Zheng also chairs the LSG for the Construction of the Greater Bay Area (GBA). Just over a year after the group was set up, it had announced 16 policy measures, including exploring the establishment of a cross-border wealth management connect, extending the scope of mutual recognition of qualifications for construction professionals, and preferential arrangements in insurance regulations between the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong. This shows the significant decision-making power many LSGs are granted.

Do LSGs make a difference?

Not all LSGs are so prolific, however, and the success of an LSG is tied to the comprehensiveness of the ministries involved in the group and the importance of the issue it covers to China’s top leadership. Moreover, Chinese media‘s reports have also highlighted that excessive use of LSGs at the local level, instead of improving efficiency, creates inefficient and redundant talking shops.

Nevertheless, the LSG for PCCN seems to have a fighting chance. In addition to its top leadership, its first meeting had a wide range of ministers and influential policymakers in attendance, including Climate Envoy Xie Zhenhua and high-level representatives from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Science and Technology, People’s Bank of China, Ministry of Natural Resources, Ministry of Transport and Ministry of Industry and Information.

Furthermore, by announcing China’s ambition to be carbon neutral by 2060 publicly at a meeting of the UN General Assembly, President Xi has tied himself to the goal. As such, the group will likely enjoy support from the very top of the political chain.

China still lacks a roadmap that lays out how its 30-60 goals can be realised. The 14th Five-Year Plan made some commitments to climate action, but vague or underwhelming targets and continued emphasis on coal led to uncertainty in the business community around how they could contribute to the energy transition. Addressing this uncertainty with clear, tangible steps will be a vital task for the LSG.

Whether the LSG for PCCN will become an influential behemoth has yet to be seen. It is far from guaranteed that the LSG will lead to rigorously implemented climate policies. However, given the importance the leadership attaches to China’s climate goal, it faces good odds.

Anika Patel

Senior Policy Analyst

anika.patel@britishchamber.cn

Sally Xu

Policy Analyst

sally.xu@britishchamber.cn